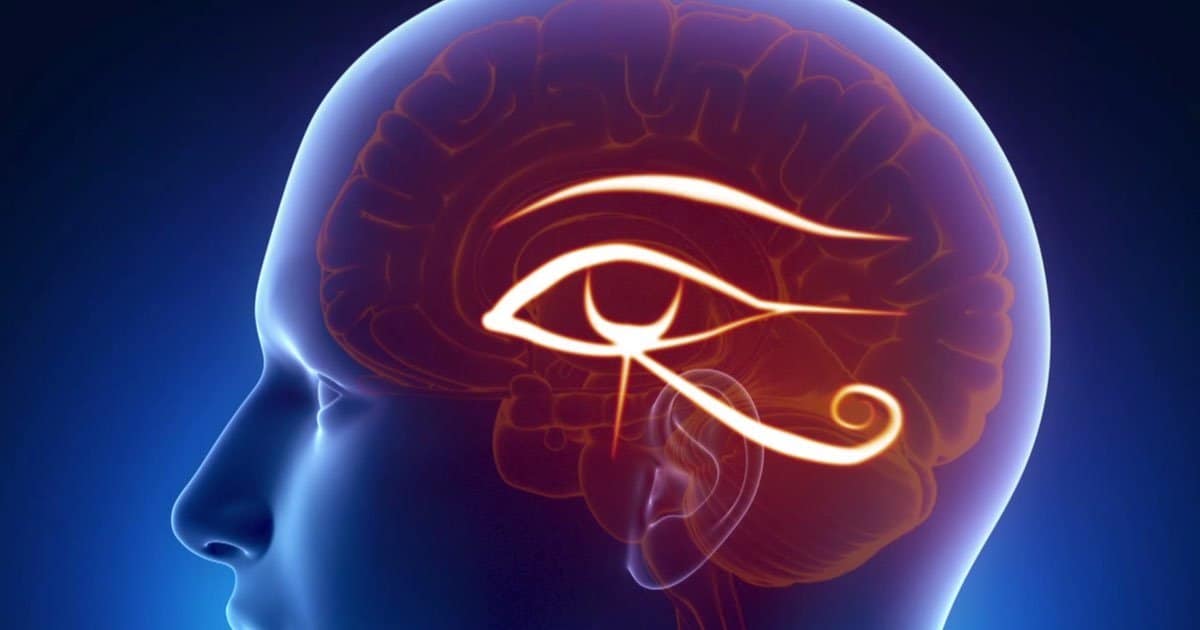

pineal gland

The name “third eye” comes from the pineal gland’s primary function of ‘letting in light and darkness’, just as our two eyes do. This gland is the melatonin-secreting neuroendocrine organ containing light-sensitive cells that control the circadian rhythm.

The pineal gland has been shrouded in mystery for millennia. To appreciate the complex sociocultural history of the pineal gland fully, we must go all the way back to the Greek physician and philosopher Galen (129–c.216). He studied it extensively, naming it after the nuts found in the cones of the stone pine. However, Galen’s understanding of the ventricular apparatus of the brain was limited. He was convinced that the ventricles contained not a fluid, but rather an airy or volatile substance that lent itself to the regulation of the ‘soul’, with the entrance to this metaphysical realm guarded by the pineal gland. These ideas persisted until the 16th century, when anatomist Vesalius (1514–1564) established categorically that no psychic phenomena flowed through the ventricles.

The 17th century ‘father of Western philosophy’ René Descartes (1596–1650) became especially enchanted with the pineal gland. He established, in his 1664 Treatise on Man, a theoretical construct for Man as containing both a physical body and also a non-physical or ‘immaterial’ mind. Influenced heavily by his staunch Christianity (which in turn incorporated dualist metaphysical frameworks from the works of Plato), Descartes was fascinated with the idea of the mind–body split and concluded that, while animals have a mechanistic body, they lack a ‘soul’.